Solar Noon

as a time

Reference

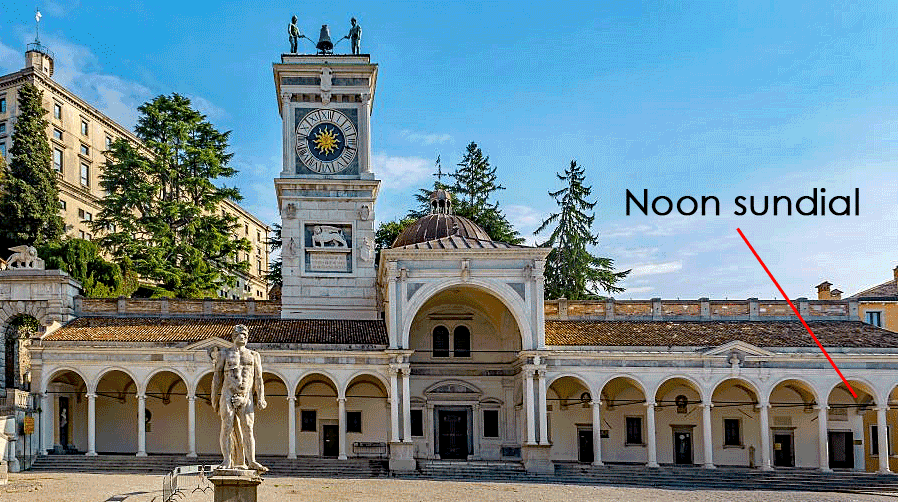

La loggia di San Giovanni in Udine features a meridian noon

sundial used to set its tower clock to read 12:00 hr. local solar

time.

Sundials like this one in Udine indicated true solar

time, the precise moment when the sun reached its highest point in

the sky and crossed the local meridian, marking

solar noon

(noon mark).

Domestic or tower

clocks were often compared -daily or weekly- with a sundial or noon

mark.

La loggia di San Giovanni

The noon sundial in Udine

The tower clock of the Loggia

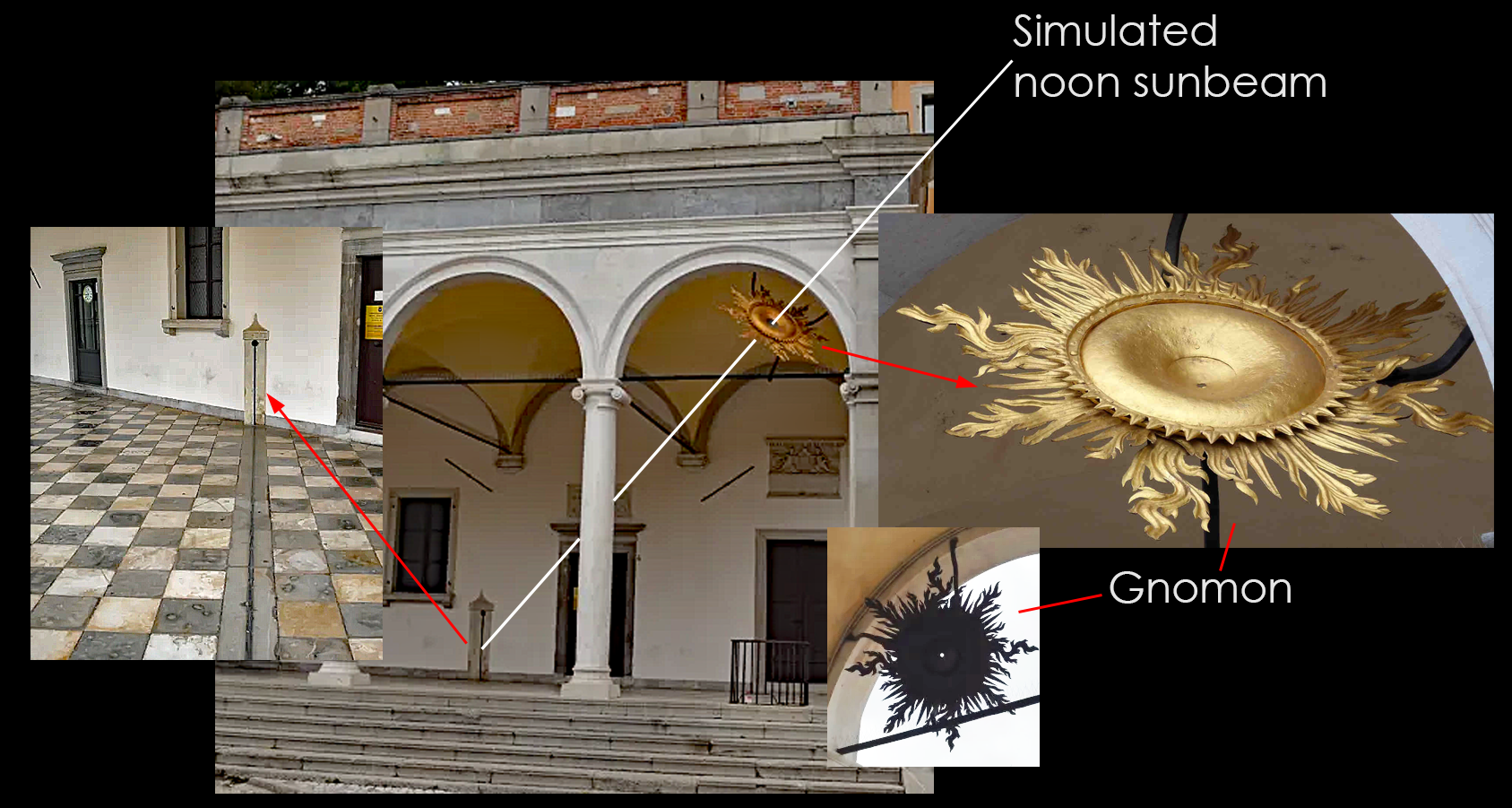

The Solar and MEAN noon

Equation of Time.

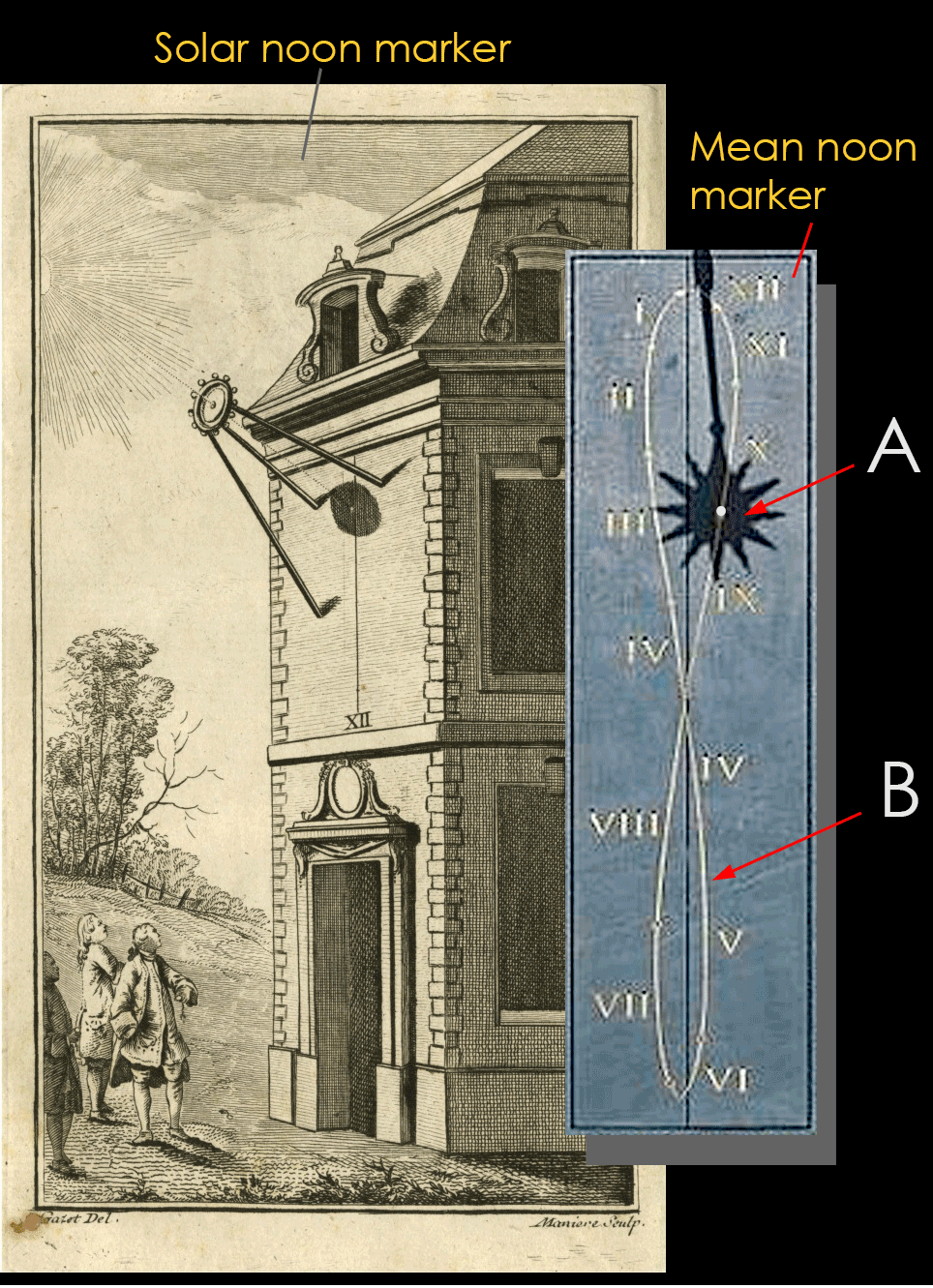

To correct for this, vertical mean noon marks were introduced.

Mean noon (clock noon) is true solar noon adjusted by the equation of time.

This type of sundial shows both true solar noon (indicated by a vertical line) and mean noon (indicated by a figure 8-curve, or analemma).

When the spot of sunlight* (A) intersects the analemma (B), the local mean noon can be read directly for the current date. In this example, the spot lies between September and October (X <> IX), indicating mid-September.

* the beam of sunlight passing through the gnomon’s small aperture is encircled by the gnomon's star-shaped shadow.

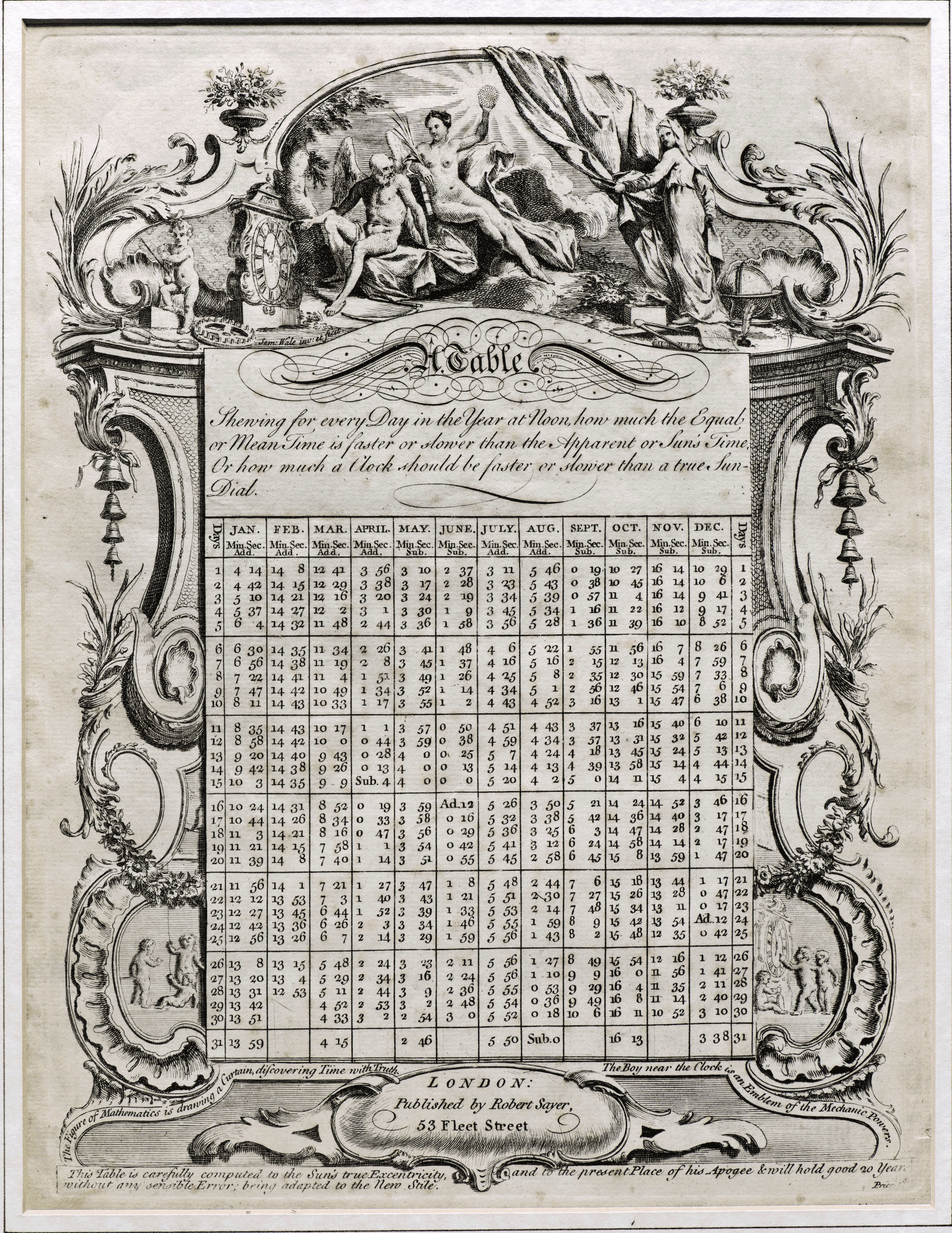

Equation tables.

Another way to handle the Equation of Time was through equation tables, which listed the daily variation throughout the year and allowed users to convert solar time into mean time.

sundial on the south face of a building in

France, c.1760.

Courtesy Mcmillan Hunter sundials.

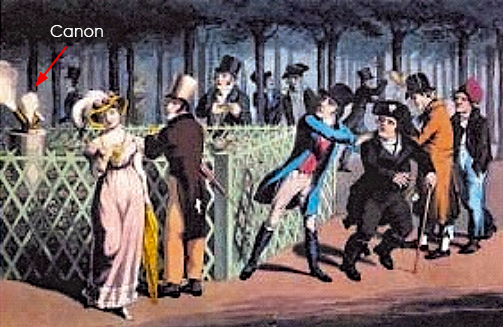

AUDIBLE MIDDAY SIGNALS

A burning glass mounted above the plate would receive the sun's rays at noon, so providing the heat to light the fuse at the end of the miniature cannon, causing it to fire and thus provide an audible signal for midday.

Cannon dials (or 'time guns' as they were occasionally known) were popular in the 18th century.

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

The 'Jardin du Palais Royal'

in Paris. Social ‘watch setting’ gathering at ‘le canon de midi’.

Jardin du Palais Royal

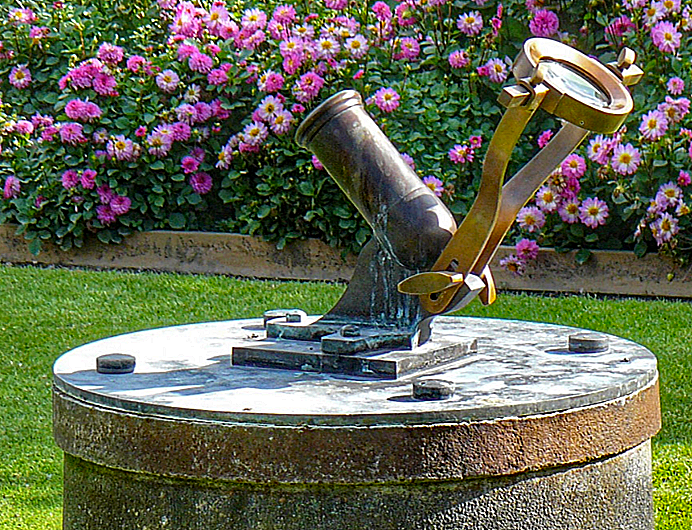

ENHANCED PRECISION

Transit instrument.

In the past used by astronomers to adjust precision clocks and watches, is a special form of a telescope mounted in such a manner and so equipped that the passage of the sun and stars across a meridian (i.e. their transit) can be very accurately observed.

Transit or southing instrument c.1840,

signed ‘Schmalcalder 82 Strand, London’

Courtesy: Flints Auctions.

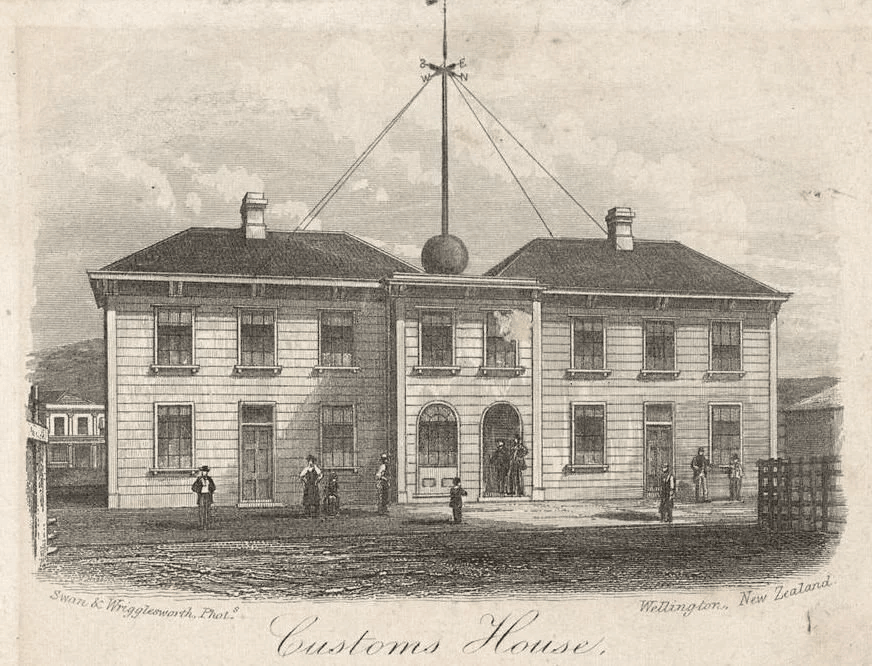

Remote synchronisation

From the 19th century onward, new tools allowed clocks to be 'synchronized remotely'

* 'Time balls' on harbor buildings (such as in Greenwich, London)

every day at exactly 1 p.m., a ball dropped so ships could set their marine chronometers.

* 'Telegraph time signals' (from about 1850) observatories sent electrical pulses to stations and cities to distribute accurate time.

Time ball on the 'Customs House'

Wellington harbour NZL.

local times

|

X

Menu

X |

| * The noon sundial in Udine |

| * The solar and mean noon |

| * Audible midday signals |

| * Enhanced precision |

| * Remote Synchronisation |

| * Local Times |

|

|

Before about 1850, each city ran on its own

local time. People simply watched the sun and called it noon when it was

highest in the sky. That meant “12 o’clock” wasn’t the same everywhere -true

noon in Amsterdam came around 12:20, while in Maastricht it was closer to 12:00.

Travellers didn’t notice much, transport was slow anyway. But with the arrival

of railways and telegraph lines, all these different local times became very

inconvenient. Consequently, countries began adopting a unified standard for

timekeeping.

In 1884, at the International

Meridian Conference held in Washington D.C,

26 nations agreed on two

key points:

1. the establishment of

Universal-Time and Time-zones, with the day defined as 24 hours

beginning at midnight, and

2. the adoption

of a single prime meridian -set at Greenwich- for international reference.

Central European Time was later introduced, first in Germany in 1893 and

subsequently adopted by many more countries such as the Netherlands and Italy.

Tobias Birch. Flints Auctions. Macmillan Hunter. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

This article is subject to ongoing updates.