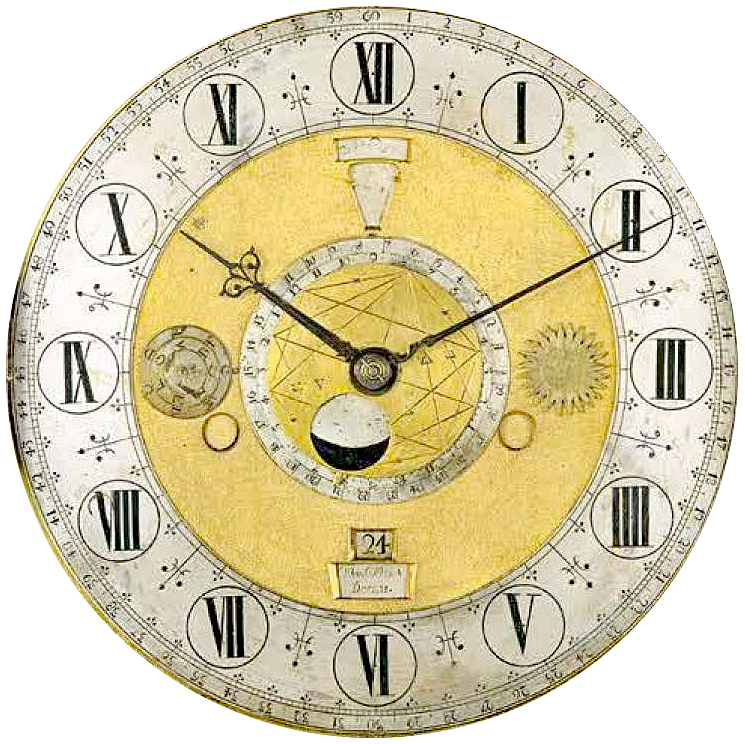

Roman Numerals on Clock Dials

|

* The compact substractive numerals * The established ancient IIII * The subtractive IV was rarely used * Roman numerals on dials through the ages Subtractive notation of Roman numerals, like IV, IX, XIV, XIX, XL evolved over time from an ancient mostly additive system and became more popular after the invention of the printing press. Although its use was inconsistent in ancient times and during the Middle Ages. While Romans initially preferred simpler additive forms like IIII for four, subtractive forms such as IV were also used, especially in inscriptions. After the printing press's arrival, the more compact forms like IV and XL gained wider use in Europe, leading to the more standardized subtractive rules that are taught today. Although they were not universally applied even by the Romans themselves. |